John Jarvie Ranch and Museum

This historic property built in 1880 provides a glimpse of turn-of-the-century frontier life in Brown’s Park. John Jarvie, a business man from Scotland, chose this particular one because of the naturally occurring river crossing. For years it had been used by Indians, fur trappers, travelers, and local residents. Jarvie figured it would be an excellent spot to establish a business. At its height, the Jarvie ranch operation included a store, post office, river ferry, and cemetery.

At the historic ranch, you’ll find the stone house, which is a one-room, rectangular building. It was built by outlaw Jack Bennett, using masonry skills he learned in prison. This is also the museum where displays decorate the walls and a video of the history of the ranch can be viewed. You’ll also get to duck inside the two-room dugout where John and his wife Nellie first lived. It is built into a hillside with a south-facing entrance overlooking the Green River. You can stroll over to the blacksmith shop and corral, which were constructed using hand-hewn railroad ties which drifted down from Green River, Wyoming, during high water. Finally, you get to pretend shop at the general store where Mr. Jarvie sold goods, which is a replica of the original which was built in 1881. It is furnished with many artifacts from the Jarvie period and also contains the original safe which was robbed from the men that murdered John Jarvie.

Visitor Information

Tour Hours

Self-guided grounds tours always available.*

Ranger tours:

Memorial Day- Labor Day available Monday – Saturday 10 am-4:30pm **

Labor Day- Memorial Day available Tuesday – Saturday 10 am-4:30pm**

Self-guided brochure & map located near restroom. Access into buildings may be limited or unavailable on Sundays and Mondays.

Due to Ranger availability, it is always best to call the Jarvie Ranch (435-885-3307) to arrange a tour.

The biography of John Jarvie and the restoration of his property, therefore, carry great potential for helping people to understand their heritage. Jarvie was a leader in his community and an important pioneer on a local level, but his fame was not national in scope. His story provides a picture of life as it existed for the common man in a frontier society; a picture that modern men can easily relate to. The Jarvie story reveals much about the nature of life in Brown’s Park, and the Brown’s Park story reveals much about society on the frontier.

The frontier, according to Frederick Jackson Turner, was the primary factor working to create unique institutions in America and unique characteristics in Americans. As pioneers entered new areas, they brought with them the politics, law, language, and culture of Europe and the East. Their culture was forced to adapt to the new environment of the frontier first by reverting to a primitive life style and eventually by discarding some ill-suited institutions and assimilating others regarded as vital. This process of rebirth on the edge of civilization gradually resulted in the Americanization of people and customs. Turner wrote: “The existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward, explain American development.”

The Brown’s Park society, due to its limited population and its isolated nature, provides an excellent laboratory for examining the Turner “frontier hypothesis.” The mountain men, cattlemen, settlers, and outlaws all moved through Brown’s Park in distinct waves reverting at first to primitive individualism and finally forming a distinct culture and cultural institutions. Mountain man rendezvous, cattlemen’s associations, and vigilante groups developed as answers to needs which could not be met by unconcerted individual efforts. Attitudes and actions were forged by the environment, Turner fashion, in Brown’s Park. The characters who populated the valley became distinctly American.

The characters of Brown’s Park, including John Jarvie, have taken on almost legendary natures over the years. However, they have not all become Owen Wister stereotypes and did not always follow the cowboy code of his Virginian. They were not all white. They were not all honorable. They were not all self reliant. They were often philosophical as well as physical. In short, they were a cross section of common citizens living day to day lives in the best way they knew how. They were Ortega’s “decisive factor” and Sheehan’s “mediocre men.” For that reason alone, the stories of John Jarvie and Brown’s Park are relevant and worth relating.

John Jarvie was born in Scotland in 1844. According to an undocumented family legend, Jarvie worked in a Scottish mine as a youth where he was severely beaten by his supervisor. When he recovered from the beating, he stowed away on a ship bound for America and bid farewell to his native land. [82] Whether he stowed away as a boy or immigrated as a young man, Jarvie had arrived in America by 1870. He settled in Rock Springs, Wyoming Territory, where he shared a residence with four other Scotch immigrants. Twenty-six year old Jarvie was the youngest of the group which included two laborers (twenty-seven year old James Strain and forty-eight year old Herbert Mathie), one coal miner (fifty-eight year old George Law), and twenty-seven year old retail liquor dealer George Young. Jarvie, like Young, was also a retail liquor dealer. [83]

Jarvie purchased the Will Wale Saloon on busy North Front Street across from the Union Pacific depot just east of the Central Hotel between J Street and K Street for $500.00. He later mortgaged the property to Moses Millington for $675.00. The Jarvie saloon was a one and one-half story frame building lined with adobe measuring twenty-four feet square. It included a dining room, kitchen, and store room. Between 1871 and 1880, he renewed his business licenses regularly. His licenses allowed him to sell wholesale liquor and retail liquor and to operate one billiard table. During 1873, he entered into a partnership with a man named McGlowin. The partnership was a brief one and by the end of the year, Jarvie was again sole proprietor of the establishment. [84]

On Friday, October 8, 1875, Jarvie appeared before the District Court of Sweetwater County. Having met the necessary residency requirements and having “behaved himself as a man of good moral character attached to the principles contained in the Constitution of the United States. Jarvie was naturalized and became a citizen of the United States. [85]

| Photo 21. John Jarvie 1844-1909. (Photo Credit: Bureau of Land Management). |

| Photo 22. “Pretty Little Nell”, Nellie Barr, married John Jarvie in 1880. (Photo Credit: Glade Ross Collection). |

Storekeeper

In 1880, at the age of 36, Jarvie married Nellie Barr, a young lady of 22 who had emigrated from the British Isles. Her family had settled in Pennsylvania, but because of health reasons had decided to move west. Enroute to Ogden, Utah, where they eventually settled, the Barrs stopped in Rock Springs long enough for Nellie and Jarvie to become acquainted. [86]

Their acquaintance may have originated in the Jarvie saloon where vaudeville type entertainment was frequently provided. “Pretty Little Nell,” as she was fondly referred to by the Brown’s Parkers, may have been a singer in the vaudeville show. Minnie Crouse Rasmussen recalled that Nellie “had a beautiful voice and used it,” while Ann Bassett wrote that Brown’s Park settlers “Mr. Davenport, Mrs. Jarvie, and Mrs. Allen [Elizabeth] possessed beautiful voices, and they sang many of the old heart songs.” [87] The marriage took place June 17, 1880, and that same year the newlyweds left Rock Springs and moved to Brown’s Park, Utah. [88] In Brown’s Park Jarvie opened a general store-trading post on the north bank of the Green River. While the store and their log house were being built the newlyweds lived in a two room dugout which was built for Jarvie by Bill Lawrence, a big, red headed Englishman. [89] The door was made of a single piece of tree trunk. The ridge log and many of the split cedar poles in the ceiling measured twelve to fifteen inches in diameter. The dugout was a cozy first home for the Jarvies in Brown’s Park.

John and Nellie moved into a three room log house just east of the dugout within a year, and the dugout became a storage cellar. In later years it would serve as a hiding place for some of Brown’s Park’s more notorious transients. Minnie Crouse Rasmussen, whose father, Charlie Crouse, had many dealings with Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch recalls: “Many people . . were interested in that [dugout] . . . . I don’t mean for anything wrong and yet the outlaws could have, you know, they very well could have [used it]. He [Jarvie] certainly saw them as much as we did.” [90]

His store was the only one within seventy miles which necessitated carrying a large inventory in order to serve the pioneer families of the area. In a very real way, the Jarvie trading post was the heir to Fort Davy Crockett which had existed some forty years earlier. Fort Crockett had been the social and commercial center of early Brown’s Hole, serving as a meeting place and source of goods for the fur traders in the same way the Jarvie post served the settlers of his day. “He sold just about everything from Indian flour, through new saddles, boots, wagon supplies, even had a pile of teepee pole for the Indians stacked outside . . . .” The Indian flour was a very poor grade of flour milled in Ashley, Utah. [91] Liquor was also a popular item.

The fact that Jarvie sold liquor gave birth to the rumor that he was once again operating a saloon. Liquor, however, was only one of the many items he sold in his store. The whiskey barrels were usually kept on a raised platform alongside the counter with their spigots ready for dispensing. [92] At other times the spirits were kept in the basement. Minnie Crouse Rasmussen remembers: “There was kind of a basement, we’ll call it, under the store where the freight was unloaded . . . the little barrel was there and maybe lots of barrels . . . .” [93]

The barrels eventually created problems for Jarvie. In 1892 he was taken to court by Sheriff Pope of Vernal, Utah, on the charge of selling liquor without a license. Two witnesses were produced who claimed to have purchased whiskey from Jarvie. The liquid was introduced as evidence and “The jury sampled the evidence and must have decided it was rot gut instead of whisky; anyway they returned a verdict of not guilty.” [94]

The following advertisement appeared in several issues of the Vernal Express:

“REWARD!

ONE HUNDRED POUNDS OF SUGAR

REWARD.

FOR EACH AND EVERY FIVE HUNDRED POUNDS OF OATS

DELIVERED AT J. JARVIE’S STORE

BROWN’S PARK” [95]

The children of George Law, one of Jarvie’s early Rock Springs roommates, eventually settled in Brown’s Park also. Daughter Jean married Billy Tittsworth and daughter Elizabeth married Charles Allen. Daughter Mary wed Charlie Crouse and settled on Crouse Creek which led to close ties between the Jarvies and Crouses. Son George Law, Jr. also moved to the Park. He might have celebrated fatherhood at the Jarvie whiskey barrels because on February 24, 1892, the Rock Springs Miner announced: “John Jarvie is in from Brown’s Park. He reports George Law the father of a bouncing boy. Mother and son are well and George in time will be all right.” [96]

As business grew Jarvie found himself in need of increased storage space. He contracted the construction of a stone building a few feet south of the Jarvie home. “Mr. Stanley Crouse . . . remembered when the stone house was built in the 1880’s. He said it was constructed by ‘Judge’ Bennett.” [97] “Judge” Bennett was actually Jack Bennett or John Bennett. He received the nickname of “Judge” when he participated in a mock trial held by Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch. An M.D. had been summoned to attend one of the Bunch. The outlaw, unfortunately, died before the doctor arrived and the kangaroo court was called to determine whether the physician was guilty of murder or not! Bennett took the role of the presiding judge and the name stuck. [98]

Bennett was not highly regarded by the people of Brown’s Park. One man who knew Bennett said “we never considered that he belonged to the Cassidy gang proper. He was a member of the hanger-on gang that followed around and got the crumbs after the Cassidy bunch had cut the loaf.” [99] Josie Bassett said that “John Bennett had been in the pen, he learned rock work there” which proved useful when he constructed the stone building for Jarvie. [100]

The Jarvies’ first child was born in 1881 and was named after his father. John Junior was followed by three other brothers (Tom, Archie, and Jim) who arrived at two year intervals to complete the Jarvie family.

Postmaster

It has often been incorrectly recorded that Jarvie was Brown’s Park’s first postmaster. [101] However, the first Brown’s Park Post Office was established October 23, 1878, with Doc Parsons as postmaster. He received an annual salary of $19.30 for his labors. In February of 1881, John Jarvie took over the position and the post office was moved from the Parsons cabin to the Jarvie property. Jarvie’s salary has been recorded as $24.98, $109.92, and $185.30 for the years 1881, 1883, and 1885 respectively. [102]

The mail came through from Ft. Duchesne and Vernal, Utah, to Green River City and Rock Springs, Wyoming, and reverse every day. “Since he [Jarvie] read all the newspapers that came in, he was an authority on any happenings on the outside . . . . Postcards, of course, were read aloud to everyone who happened to be around.” [103] The Jarvie post office, however, was to last only six years.

On June 8, 1887, the post office was closed. Jarvie had been asked to investigate some suspicious dealings including improper accounting for money orders taking place in the Vernal, Utah, post office under the direction of a postmaster by the name of Kraus. Jarvie did not wish to spy on a fellow postmaster and, instead, he packed up all of his records and paperwork and closed the Brown’s Park post office. “Mr. Jarvie put all the pens and inks and paper and all the books and everything in a sack and sent it in and that was all of the post office. He told me this himself,” recalls Minnie Crouse Rasmussen. [104]

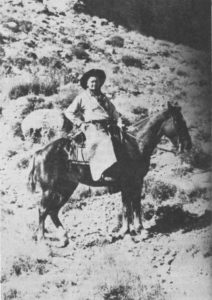

| Photo 23. John Jarvie in a rare photo showing him without his usual full beard. (Photo Credit: Glade Ross Collection). |

Ferry Operation

In addition to his responsibilities as postmaster and storekeeper, Jarvie became a ferry operator in 1881. When Doc Parsons (previous ferry operator) died “John took over the ferry, which is usually known by his name. The first wool shipped from Ashley crossed the Green on Jarvie’s ferry.” [105]

An article in the Vernal Express, April 21, 1898 states that

to accommodate the settlers of Ashley Valley, who sometimes travel through the Park and are short of cash, Mr. Jarvie announces that he will take any kind of farm produce in pay for ferrying bills, which will be appreciated, no doubt, by a great many, and give none an excuse to endeavor to beat their way across the river. [106]

Jarvie’s ferry operated from 1881 until his death in 1909. During the last couple of years the flatboat ferry was replaced by a hand operated cable car. [107] For a brief period of time during the early 1900s the Jarvie enterprize was put out of business when Charlie Crouse built a bridge a short distance downstream and established the small town of Bridgeport. (“Crouse charged $1.00 for team and wagon, $1.50 for 4 horse team, and 50¢ for a saddle horse . . . to cross his bridge.” [108]) During this period Jarvie mentions his situation in letters to his sons: “The Bridge has been finished for some time and the Ferry is lying in the river unused. I did not take the trouble to fix it this year,” and “Crouse has a Bridge where Gray’s Ferry used to be, and a P. Office and store. So I have very little to trade, and the ferry has not run for two years, but it does not take much to keep me here.” [109] Luckily for Jarvie the Crouse bridge was shortlived. It lasted only a couple of seasons before it was destroyed by an ice flow. [110]

| Photo 24. A ferry near Moab, Utah, which was similar to the Jarvie ferry in Brown’s Park. (Photo Credit: Utah State University Special Collections). |

On one occasion Larry Curtin and Matt Warner attempted to cross the Green River on Jarvie’s ferry. Instead of dismounting, Curtin, puffing on a cigar butt, rode his horse onto the flatboat. In the middle of the river the horse reared and fell into the high swift water along with his rider. Matt tossed him a rope and “While the horse swam to shore, Matt pulled Larry aboard. The cigar butt was still firmly in place.” [111]

Jarvie employed many of Brown’s Park’s colorful characters as either freighters for his store or ferry operators. Albert Williams, a black man, affectionately known as Speck (short for Speckled Nigger) due to his mottled complexion was one of the Park’s best liked citizens. Speck “ran Jarvie’s ferry for quite a spell.” [112] Charlie Taylor and his young son Jess, Henry Whitcomb Jaynes, Harry Hindle (a diminutive Welshman who was famous for his plum duff), and Jim Warren freighted for Jarvie. Outlaw Matt Warner worked on the ferry at times. [113]

| Photo 25. “Speck” Williams often operated the ferry for Jarvie. (Photo Credit: Utah State Historical Society). |

Mining Interests

While Jarvie’s major sources of income were the store and the ferry, he also had mining and livestock interests. On February 20, 1897, Jarvie, along with Sterling D. Colton and Reuben S. Collett, purchased Addeline Hatch’s half interest in the Bromide Lode Mining Claim on Douglas Mountain, Routt County, Colorado, for $25,000.00. From Lorenzo Hatch Jarvie purchased an undivided 1/4 interest in the same claim as well as undivided 1/4 interests in the Sand Carbinet Lode Mining Claim and the Durham Lode Mining Claim for a total of $17,550. Jarvie, Colton, Collett, and S.M. Browne also located and claimed the Side Issue Lode Mining Claim, the Bromide Number 2, and the Hidden Treasure Lode Mining Claim, all on Douglas Mountain. [114]

Unfortunately, the mines never paid off and the partners were forced to sell out to the Bromide Mining and Milling Company in 1898 at a tremendous loss. Jarvie was never able to recover from the financial burden which resulted from the mining ventures. In his words: “I had borrowed about $5,000.00 dollars from the banks in Rock Springs thinking I would make something out of the Bromide at Douglas . . . it did not pan out.” [115]

In spite of his poor luck he continued to prospect in the Brown’s Park area until the time of his death, always searching for that elusive strike. Corresponding with his son John, he tells of “sinking holes here and there in search of the vein. And last year I feel sure I discovered it, but I only got down about 15 feet. And it looks ever so much better than anything over at the Bromide.” He goes on to say, “I have done quite a lot of development around here . . . . I found a fissure on the Apex of the Jetma and drove a tunnel in for 150 ft. but never got into solid vein matter,” and “You remember we occasionally found gold, or thought we did, well I think I have found some again . . . .” [116]

While prospecting in Red Creek Canyon in March of 1903, the strap that held the cinch on his saddle broke and he took a serious fall down a steep cliff side breaking four ribs. He suffered the pain for a while and finally went to the doctors in Rock Springs where they wrapped his body with adhesive tape without first shaving his very hairy chest. Returning to the Park, he began to experience a terrible itching and enlisted the service of young Minnie Crouse to help remove it from his body. Minnie recollected the event: “We were pulling it off and it was a terrible thing and I got the giggles. I got around him and though he couldn’t see me, he got very mad at me, but we finally got that off. It was torture.” [117] After the tape was removed, he went into his store and brought out a woman’s corset. Minnie helped him get it on and laced it up and he wore that until the ribs had healed.

Livestock Interests

In 1892 John Jarvie and James Scrivner went to Texas to buy sheep. [118] Jarvie, however, never got involved in the sheep business. His livestock interests centered around horses and cattle. His cattle herd was never very large. In 1888 he had fifteen head, in 1890 he was down to six. At the time of his death in 1909 he had his largest herd on record: 75 head valued at $1,500.00. [119]

He raised only a few horses. In 1888 he had six. In 1890 he had ten and in 1909 he had only two. He did, however, go into business with George Law in Routt County, Colorado, in the 90s and in 1897 they had a herd of 142 horses valued at $1,456.00. [120] Jarvie and Law were the largest horse owners in the Colorado end of Brown’s Park. The total number of horses was 265 of which well over half belonged to Jarvie and Law. Herb Bassett was second largest horse owner with only thirty. Anton Prestopitz, Isom Dart, and Jim McKnight with twenty, fifteen, and ten horses, respectively, completed the list of the top five horse owners. Ads appeared in local papers reading, “Anyone wishing to trade land for horses will do well to address John Jarvie and Law, Ladore, Colorado.” [121]

Jarvie constructed corrals and stables for his livestock. According to Ann Bassett, a prospector by the name of Minor may be buried under the Jarvie corrals. [122] The structures were partially constructed out of hand hewn railroad ties which would occasionally float down the Green River from the City of Green River in Wyoming. Jarvie and other Brown’s Park residents would retrieve them and put them to good use.

Next to the corrals Jarvie built a one-room blacksmith shop of cottonwood logs. He not only did his own blacksmith work, but would occasionally do custom work for his neighbors. Crawford MacKnight remembers that Jarvie was “a damn handsome man, he did damn fine work [for himself] and damn fine custom work, too.” [123]

To irrigate his pasture Jarvie constructed a large waterwheel some sixteen feet in diameter. Buckets on the paddles dropped water into a flume which carried it to a system of ditches.

Land and Business Dealings

Jarvie performed civic duties as an election official in the Brown’s Park election district of Uintah County. In 1904 he served along with Charlie Crouse and M. F. Whalen and was compensated $4.00 for his labors. In 1906 he served with George Kilvington and James Greenhou and received $3.75. By 1908 he had become the district registration officer and earned $15.00. [124]

In addition to his original property, Jarvie acquired other land throughout the area in Utah and Colorado. In Utah, Jarvie obtained the old Parsons property by irrigating it as a Desert Entry with the water from Sears Creek beginning in 1887. In 1902 he was granted a patent on the 83.72 acres which he, in turn, sold to Charlie Taylor in 1907 for $500.00. In 1907 he purchased 27.5 acres of land near Vernal, Utah at a tax sale for $11.70, the amount owed in back taxes. This piece of property was eventually sold by Jarvie’s sons following his death to Thomas Brumback for $450.00 in 1911.

In Colorado, Jarvie owned roughly 240 acres. He purchased 80 acres from Jane Jaynes (Brown’s Park’s first school teacher) in 1889 and another 80 acres through a tax sale in 1892. In 1900 he purchased 78 acres (more or less) from Henry Hindle. All of the Colorado property was eventually sold by his heirs for minimal amounts or purchased by redeeming parties through tax sales. [125]

On at least three occasions, Jarvie loaned money in the form of mortgages to his neighbors. The first loan took place October 16, 1886 when Matt Warner mortgaged 124 horses to Jarvie for $847.90 which was to be repaid by April 16, 1887, at 12% interest per annum. On February 8, 1889, Joseph Toliver mortgaged all of his cattle to Jarvie for $538.00 which was to be repaid by September 8, 1889, at 12% interest per annum. Finally, Sam Bassett and Thomas Shackett mortgaged property known as the Aalbion Beaty Ranch in Ashley, Utah, to Jarvie on March 7, 1894. The debt was discharged October 2, 1896, at the rate of 10% per annum. Interestingly, the mortgaged property was the same property Jarvie was to purchase at the tax sale in 1907 for $11.70. [126]

Although he resided in the Utah side of Brown’s Park, Jarvie’s dealings and land holdings in the Colorado section placed him on the Routt County tax assessment rolls. The 1897 roll indicates Jarvie’s relative position among the Brown’s Parkers of Routt County. Out of twenty-eight tax payers, Jarvie (combined amounts assessed John Jarvie, Jarvie and Company, and Jarvie and Law) ranked eleventh in the value of real estate with $515.00 which was substantially less than J.S. Hoy who topped the list at $4,850.00 but much closer to Henry Hoy who was second highest with $993.00 or Herbert Bassett who was ninth with $615.00. In personal value, Jarvie ranked fifth with $1696.00 coming in below Herbert Bassett ($3,402.00), Charlie Sparks ($2,349.00), Matt Rash ($2,120.00), and Sam Spicer ($1,944.00). Jarvie also ranked fifth in total value with $2,211.00 coming in below J.S. Hoy ($4,930.00), Herbert Bassett ($4,017.00), Charlie Sparks ($2,804.00), and Sam Spicer ($2,740.00). [127]

Musician, Athlete, Scholar, Head Reader

Jarvie was not all business, however. His personality is revealed through his hobbies and interests. He was something of a gourmet chef, always ordering gourmet items for himself through his store. His specialties were mourning dove pie and his oatmeal. [128]

Jarvie was sometimes known as “Old John” because his hair had turned snow white in his twenties. He tried to grow his hair long once because a New York wig maker was paying for hair a foot long. Although he “was very anxious to do that,” he “never could get it long enough.” [129]

His hobbies were chess and higher mathematics and phrenology. Minnie Crouse Rasmussen recalled: “He read our heads. He couldn’t keep his hands off people’s heads. [Through phrenology he could tell] . . . your character, your feelings, and your good standards . . . whatever that skull tells you. He liked to do it.” [130]

He not only read skulls, but he was also an avid reader of books. He had a fine library and would often loan books to his neighbors. Jarvie and Herbert Bassett would often sit up until the early hours of the morning discussing the classics around the fireplace at the Bassett ranch. [131]

His musical talents were well known in Brown’s Park and he was always in demand at social functions where he played the organ and the concertina. He “could play the old fashioned organ (of which there were several in the country at that time) over a hundred pieces of music from memory—Scotch ballads, Irish love songs, patriotic music, and hymns . . . . Being a Scotchman, he was always called upon to recite some of Burns poems which he enjoyed so well.” [132]

Because of his Santa Claus appearance and his kindly nature, the children of Brown’s Park took a special liking to Jarvie. Ralph Chew recalls: “We kids thought Jarvie was the greatest man alive. He had a long beard and always had candy for the children. We used to love to visit his store.” [133]

Even as he advanced in years, Jarvie was something of an athlete. He was an early day jogger and skater. Jess Taylor remembered that Jarvie could “run like a deer” and was always trying to engage the local youngsters in footraces. Crawford MacKnight conjures up a strange picture of Jarvie, with flowing white beard, ice skating through Brown’s Park on the frozen highway of the Green River (Skating through the Park was not an unusual mode of transportation; children often found it to be the quickest and most convenient route to and from school). [134]

“Pretty Little Nell” died in the Jarvie home of tuberculosis in the arms of Elizabeth Allen circa 1895 when the youngest of the four Jarvie boys was only eight years old. She was buried in Ogden, Utah, where the Barr family was living. From the day of her death until the day of his own, John Jarvie kept his wife’s possessions just as she had left them; the clothes hanging, the jewels on the dresser, etc. [135]

Thus John Jarvie became both father and mother to his sons, John Jr., Archie, Tom, and Jimmy, when they were still young boys. In spite of helpful offers from the neighboring Brown’s Park women, Jarvie single-handedly took care of his children. Minnie Crouse Rasmussen recollected: “He made their clothes, he had a sewing machine . . . I suppose it was a Singer . . . . He even sewed buttons on with that . . . everyone marvelled at it.” [136]

On December 1, 1892, Jarvie made the delinquent tax list for Uintah County. His debt was the second highest on the list ($46.50). He was in good company. The list contained the names of many of Uintah County’s most prominent citizens. [137]

In 1901 J.S. Hoy gave a Christmas dance at his ranch. Among the guests were the Chew bunch, Ann Bassett and her brother Eb, Josie Bassett McKnight, John Jarvie, and Joe and Esther Davenport. Thirteen year old Avvon Chew, one of the many Chew’s family children, had a crush on Eb Bassett who had recently returned from Chilicothe College. John Jarvie donated a cigar band which Eb placed on her finger in a solemn ceremony. Avvon was in seventh heaven! [138]

When Jarvie’s good friend and neighbor Mary Crouse died in 1904, Jarvie wrote a very warm tribute to her. It contained the following lines: “Here in this world where life and death are equal kings, all should be brave enough to meet what all have met . . . . in the common bed of earth patriarchs and babes sleep side by side . . . . I should rather live and love where death is king than have eternal life where love is not.” [139]

Matt Warner’s Masquerade Party

While John Jarvie knew most of the outlaws who frequented Brown’s Park, he helped, indirectly, to launch young Matt Warner’s life of crime. Matt had heard from Elza Lay that a Jewish merchant was transporting his goods through Brown’s Park. He had gone broke in Rock Springs and was making his getaway before the sheriff could attach his merchandise. Matt decided to hold up the merchant and relieve him of his goods since the storekeeper would be in no position to complain to the law.

Having thus acquired the goods, which were mostly items of clothing, Warner hit upon a unique method of distribution. He took them to John Jarvie’s store and told him to distribute them from that point and tell everyone to come to a big masquerade dance wearing the “hot” items.

Soon everyone in Brown’s Park had heard of Matt’s plan and everyone was laughing about it. “It ain’t on record either that anybody refused to take the stolen goods. Every last man, woman, child, and dog in the valley . . . come to the dance dressed in them cheap, misfitting clothes.” [140]

Jarvie had done an excellent job distributing and misfitting the clothing. In Matt Warner’s words:

It was the funniest sight I ever saw in my life . . . most of the people persisted in hanging onto parts of their old cowboy and rancher outfits and mixing up clothes dreadfully. The way store clothes and cowboy clothes, celluloid collars and red bandanna handkerchiefs, old busted ten-gallon range hats and cheap derbies, high-heel boots and brogans, Prince Albert coats and chaps, and spurs and guns was mixed up would give you the willies. One old weather-beaten rancher was dressed like a minister, except he had his gun belt and gun on the outside of his long black coat. A cowboy was dressed like a gambler with a bright green vest and high hat, but persisted in wearing his leather chaps, high-heel boots, and spurs. A weather-beaten ranch woman, with a tanned face, and hands like a ditch digger, had on a bridal veil and dress with a long train. A big cowgirl come with a hat on that looked like a flower garden, a cheap gingham dress, and brogans.

Everytime someone arrived, there was a lot of hollering and laughing and clapping and stomping, and someone would yell, ‘Here comes another Jew!’ The lone fiddler scraped his fiddle and stomped time . . . There was so much noise and fun you couldn’t hear yourself think. It kept up that-a-way till daylight and everybody was wore out. [141]

Thus Matt Warner’s career as the “Last of the Bandit Riders” was underway.

| Photo 26. Matt Warner supplied the costumes for Brown’s Park Masquerade Party. |

Outlaws’ Thanksgiving Dinner

On at least one other public occasion Jarvie mingled with the outlaws. He presided over the “Outlaws’ Thanksgiving Dinner” ca. 1895. According to “Queen of the Cattle Rustlers,” Ann Bassett, it was the only real formal affair ever held in Brown’s Park.

It was on that holiday occasion that the outlaws who frequented Brown’s Park decided to repay their neighbors for their kindness, generosity, and live-and-let-live policy of co-existence. Billie Bender and Les Megs (leaders of the Bender Gang; agents for smugglers working from Mexico to Canada) along with Butch Cassidy, Elza Lay, Isom Dart, and the Sundance Kid put on a spread that would thereafter be known as the “Outlaws’ Thanksgiving Dinner.” [142]

The burning question in Brown’s Park was what to wear to this elegant affair. The men wore dark suits and vests, stiff starched collars, and bow ties. Mustaches were waxed and curled. The women wore long tight fitted dresses with leg-o-mutton sleeves and high collars. The older ladies wore black taffeta and high button shoes with French heels while the younger girls wore bright colors.

Ann Bassett recalled her attire as being a

silk mull powder blue accordion pleated from top to bottom, camisole and petticoat of taffeta, peterpan collar, buttoned in the back puff sleeves to the elbows . . . The mull pleated well and how it swished over the taffeta undies . . . for the stocking — hold your hat on and smile — lace made of silk and lisle thread black to match shoes. They were precious and worn only for parties . . . they cost $3.00 per pair and lasted a long time. [143]

The dinner was held at one of the Davenport ranches on Willow Creek. The best silver, linens, and dishes had been loaned by the Brown’s Park ladies and Elizabeth Bassett’s silver candelabra graced the table.

Les Megs, Billie Bender, and Elza Lay received the guests at the door and later joined Butch Cassidy and Sundance, dressed in white butcher’s aprons, to wait on the tables. Isom Dart, in a tall chef’s hat, presided over the kitchen. The group of guests was a very cosmopolitan one. Among the relatively small number, the nations of Scotland, England, Ireland, Australia, Sweden, Yugoslavia, Wales, Mexico, Canada, Italy, and Germany were represented as well as several states.

The evening’s program began with the invocation given by John Jarvie. Ada Morgan and Mr. Davenport sang “Then You’ll Remember Me” and “Last Rose of Summer” accompanied by Jarvie on the accordion. Josie Bassett played “The Cattle Song” on her zither accompanied by a fiddle and guitar. Ann Bassett gave a short reading on the meaning of Thanksgiving (after having been coached by Jarvie for a couple of weeks).

When the guests were finally seated, Jarvie asked the blessing from his place of honor at the head of the long table and then the meal was served. The menu included blue point oysters, roast turkey with chestnut dressing, giblet gravy, cranberries, mashed potatoes, candied sweet potatoes, creamed peas, celery, olives, pickled walnuts, sweet pickles, fresh tomatoes on crisp lettuce, hot rolls and sweet butter, coffee with whipped cream, and Roquefort cheese. For dessert they had pumpkin pie, plum pudding with brandy sauce, mints and salted nuts.

Ann Bassett remembered the trouble Butch Cassidy had pouring the coffee:

Poor Butch, he could perform such minor jobs as robbing banks and holding up pay trains without the flicker of an eyelash, but serving coffee at a grand party that was something else. The blood curdling job almost floored him, he became panicky and showed that his nerve was completely shot to bits. He became frustrated and embarrassed over the blunder he had made when some of the other hosts . . . told him it was not good form to pour coffee from a big black coffee pot and reach from left to right across a guests plate, to grab a cup right under their noses. The boys went into a huddle in the kitchen and instructed Butch in the more formal art of filling coffee cups at the table. This just shows how etiquette can put fear into a brave man’s heart. [144]

The dinner party lasted about six hours after which the group adjourned to the Davenport home for a dance. They danced until the sun came up the next day!

In a letter describing the placement of guests at the dinner, Ann Bassett had this to say:

Mr. Jarvie should be given the place of honor for he was a darling. He was jolly and gay and everyone young and old loved him. His tragic death cast a deep gloom over the entire country from Vernal to Rock Springs. He was one of the truly great characters that ever lived in the park. Next to my father I think he was the person near perfect. [145]

“Jerked to Glory”

An event took place in Brown’s Park in 1898 which had a lasting effect upon the outlaw population there. Although it did not take place on the Jarvie ranch, there are a several direct ties with the property. Speck Williams was operating Jarvie’s ferry when a prospector by the name of Strang asked him to look after his young son, Willie, while he went to town for supplies. Willie soon grew bored on the river and took off with a fellow by the name of Pat Johnson who was living at the Valentine Hoy ranch on upper Red Creek.

Willie spent a night at the Hoy ranch in the company of Pat Johnson, “Judge” Bennett (who had constructed the stone house at the Jarvie place), Charley Teeters, and Bill Pigeon. Throughout the night the men drank and joked with each other. Early the next morning, in the same spirit, seventeen year old Willie played a joke on Johnson. He either pulled a chair from under him as he was sitting down, kicked him in the seat of the pants, or splashed him with water from a dipper. [146] Johnson was not in the same jocular mood he had been the night previously and as young Willie ran outside to feed his stock in the stables, Johnson drew his revolver and fired at the boy. The bullet lodged in his spine and he fell to the ground. Mr. and Mrs. Blair, Hoy’s in laws, heard the shot from their upstairs room. Mr. Blair rushed to the window and “saw the young man stretched out in the snow . . . . Immediately after the report of the pistol he heard the words ‘Oh, God! Oh, God!'” [147] Willie soon died and Bennett and Johnson immediately left for Powder Springs on horses belonging to Hoy. [148] At Powder Springs, Bennett and Johnson met Dave Lant and Harry Tracy, recent escapees from the Utah penitentiary. [149] The quartet decided to head for Robbers’ Roost. Bennett went for supplies and arranged to meet the others near Douglas Mountain.

| Photo 27. Dave Lant. (Photo Credit: Utah State Historical Society). |

| Photo 28. Harry Tracy. (Photo Credit: Utah State Historical Society). |

Meanwhile, Sheriff Neiman and Deputy Ethan Allen Farnham of Routt County, Colorado, arrived in Brown’s Park. They had come to arrest Bennett and Johnson for illegal activities which had taken place in Colorado. Learning of the Strang killing, they quickly formed a posse of Brown’s Park men including Eb Bassett, Valentine Hoy, Jim McKnight, Joe Davenport, Longhorn Thompson, and Bill Pigeon and the manhunt was on. [150] The posse found the fugitives’ camp. Horses, blankets, and food had been left behind indicating a hasty departure. Sheriff Neiman reasoned that the outlaws would not last long without any supplies during the freezing March night. So the posse gathered up the abandoned gear and headed to the Bassett ranch for the evening.

The following day the posse again approached the trapped outlaws. Valentine Hoy was in the lead. Suddenly “the report of a rifle fractured the frosty air. Shot through the heart, Hoy slumped to the ground. Within seconds, the snow surrounding his body was crimson. Death was instantaneous.” [151] Unfortunately for Bennett, he had selected this moment to arrive on the scene with the supplies for the trip south. He dismounted, fed his horse some oats, walked to a knoll, and “discharged his six shooter three times, waited a few moments as if for an answer to his signal and fired his rifle once.” [152] Instead of the Powder Springs gang which he had hoped to meet, he was captured by Eb Bassett and Boyd Vaughn, taken to the Bassett ranch, and put under guard by Deputy Farnham.

The next day, after the posse had left to retrieve Hoy’s body, Josie Bassett McKnight’s small son, Crawford, cried out, “Mommy, look at the funny men!” A small party of seven men with hastily manufactured masks had ridden up to the ranch. “Josie remembered one man masked in the sleeve of a slicker with eye holes cut out.” [153]

The vigilantes found Farnham and Bennett and demanded obedience of the officer. “Leaving one man to guard the under sheriff, the remainder took Bennett in the yard . . . . He weakened when the mob took him and begged piteously for his life, promising to divulge everything.” [154]

Bennett was taken to the corral where the posts framing the gate reached a height of about twelve feet tied together at the top by a cross member consisting of a substantial pine pole. “They stood him up in a springboard buggy, put the noose around his neck and when they were already, pulled the wagon out from under him and let him hang.” [155] “The drop was too short to break Bennett’s neck and for three or four minutes he danced a lively jig in midair, gyrating and pirouetting grotesquely. Then . . . there was one less trouble-maker in Brown’s Park.” [156]

Sometime later, a poem was found in Bennett’s pocket. It had been written by fellow outlaw Lant describing his escape from the Utah penitentiary.

We left the Salt Lake pen

As the sun was setting low;

And walked along the railroad track

Until our legs refused to go.

But we reached Park City early.

Where the morning sunbeams lit

On our striped pantaloons,

Where a happy party sit.

Its there we took to refuge,

And watched the brave policemen,

While around us they did tear.

Its there we ate our lunches,

And our weary limbs did rest;

Until the sun was sinking

In the far and distant west.

When we started on our journey.

For our home we call the wall;

Where very few detectives

E’er dare to make their call. [157]

The killing of Hoy brought men from three states pouring into Brown’s Park to join the manhunt. The Colorado group was led by Neiman and Farnham. The posse from Vernal, Utah, was under the direction of Sheriff Preece while the men from Sweetwater County, Wyoming, followed Deputy Sheriffs Peter Swanson and William Laney. [158] Excitement ran high and a Rock Springs paper forecast “there is no doubt that the murderers will be shot or lynched as soon as captured.” [159]

| Photo 29. Grave of “Judge” Bennett, victim of Brown’s Park only lynching. (Photo Credit: Utah State Historical Society). |

It did not take long, however, for the freezing, starving outlaws to give themselves up. Their feet were bare and bloody. They had had to kill a colt for food. “Johnstone was the first to throw his hands up then Lant did likewise, but Tracey made him pull them down again under a threat of killing him right there. Shortly afterward, however, both gave themselves up.” [160]

A hearing was conducted by Justice J.S. Hoy, brother of murdered Valentine, in the Bassett living room. Johnson was taken to Rock Springs and Tracy and Lant were taken to the Routt County jail at Hahn’s Peak. With the outlaws safely behind bars, the governors of the three states met in Salt Lake City to congratulate themselves for the joint effort at law enforcement and to formulate plans for future action against other outlaw gangs. During the conference, a message from the outlaws in the Brown’s Park area was delivered to the governors which, as Governor Adams put it, “intimated they were ready for us and we could not suprise them.” [161]

J.S. Hoy wrote a letter of thanks to the people of Uintah County who helped so courageously to capture the murderers. He felt, however, that they would probably soon escape again or be given very light sentences and soon be out among society to commit more crimes. [162] Living up to Hoy’s expectations, Lant and Tracy surprised Sheriff Neiman in the Hahn’s Peak jail, beat him into insensibility, robbed him, and fled. They were recaptured after a few hours of freedom.

Certain Routt County citizens, fearing the cost of an extensive trial in their county, urged that Lant and Tracy be sent back to Utah to finish their prison terms before the trial was held. However, popular sentiment favored a Routt County trial. The prisoners were, however, moved from Hahn’s Peak to the jail in Aspen since the cost of their “lodging” there was only two dollars per day instead of the $3.50 to $4 per day at Hahn’s Peak. [163] They eventually pulled the same trick on the jailer in Aspen and escaped from that prison.

Johnson was tried for the murder of Willie Strang and was freed by the jury. Tried as an accomplice to the Hoy murder, he was sentenced to ten years, served two, and was released. Lant “enlisted and received a citation for bravery in the Philippines.” Tracy “blazed a trail of robberies and murders across the Northwest, killed three guards in a prison break in Oregon, and finally put a bullet through his own head rather than give up.” [164]

Letters to Sons

The best insight into John Jarvie’s personality and attitudes can be found in his own words in letters which he wrote to his sons after they left home. From a letter to John Jarvie, Jr., May 28, 1902:

I am well, also individually alone. The boys appearingly have all made a mistake when they chose me for their father. And each and every one, as soon as they were able, or thought they were able to be a father to themselves have left, and I candidly believe that all left with the idea that I was unfit to be father to them. Perhaps they are right, I admit I was hard to please, and wanted to see everything done away ahead of what the average boy could do. I sure had a strong desire to see my children excel in everything that was good and clever, and while everything has been backwards with me since I entered into the mining or prospecting business, yet not anything has hurt me mentally like my boys all repudiating my right to boss, or that I was capable of directing them. Yet I still think, that it will all come out for the best. [165]

He mirrors these same sentiments in a letter to Tom:

I must say it was a hard blow to me when you all left, and hurt me more than ever I said, but for all that, it would have pleased me very much to have seen you all doing well, behaving yourselves as gentlemen, and getting ahead in the world . . . . I do not think any of you boys realized my position when you left . . . I wanted to save all I could to pay up my debts. And I did not want to lay out money on anything I thought we could get along without, and possibly you boys thought it was just my disagreeable way, and that I was not treating you exactly right when really it was for your sakes I invested what money I had . . . thinking that in a short time I would be able to send you all to some first class school and so give you a good education . . . . [166]

Realizing that his interests in Brown’s Park were too much for a lone, aging person to handle, he attempted to persuade his sons to return. To Tom he writes: “I really need someone to help me, but I expect it will have to be some one else than any of my boys, and it must be that I deserve it . . . . If ever you feel like coming home, I promise to do the best I can by you.” [167]

To John he writes: “I offered Archie a half interest in the cattle and their increase if he would come and look after them for two years, but he would not . . .” and “if ever you feel like it, will be pleased to see the son (and the sons) and the father united more closely than ever.” [168]

His values are reflected in the advice he offers to his son Tom. “I sincerely hope you will use every opportunity presented you to learn, learn everything that comes before you, it is always of use even when you think differently . . .

I think you will be a good man . . . learn also to be a useful man. Then all will be well.” [169]

He offers John, Jr., these thoughts on his twenty first birthday:

My how time passes. You . . . have been enjoying a man’s estate for a long time past and I do not think I need say a word in regard to advice or council to you at all, even should you care to take it. Your habits are getting pretty well fixed and are part and parcel of your character, your individuality. And I do not think any one will be able to accuse you of lacking in veracity, or integrity, or efficiency and that is sure a fair start in life for you . . . I think you will be pretty hard to beat as an all around efficient man for almost anything; be sure and endeavor not to go to extremes in anything . . . . Yours with the best wishes and love that is in me. John Jarvie. [170]

“Foul Murder in Brown’s Park”

John Jarvie’s ranch was somewhat of a way station for pioneer travelers. Esther Campbell believed that “He kept people overnight quite often who would come here to cross the ferry and couldn’t go on . . . this place was the stopping place between Vernal and Ft. Bridger.” [171] It was probably in this manner that he first met George Hood in 1908. “During the winter Mr. Jarvie had given a man named Hood lodgings and food (some wages) to help around the store. Hood [was] not worth much but Jarvie had befriended him.” [172] Hood was a sheepman who had herded sheep in the area during the summer of 1908. [173] “When Hood worked for Kendall and Whelan . . . he had been in the habit of visiting the Jarvie ranch and had on two occasions stopped overnight.” [174]

Hood and a partner of his are thought to have stolen some horses from the Cary ranch near Hayden, Colorado, early in the summer of 1909. [175] That same summer Hood arrived at Speck’s place with word that Whelan, who had rented out a band of blackface bucks to Williams, wanted the bucks moved to Red Creek. The agreeable Speck gave the bucks to Hood who then drove the whole band to Rock Springs where he sold them and went on a wild spree. Speck Williams did not have much admiration for Hood’s cowboy ability. He said that Hood “always broke his horses tied to a tree.” [176]

In spite of his financial reverses, the rumor persisted that Jarvie had large amounts of money in his store safe or concealed on his property. One story tells of a man by the name of Jim Nicholls who stopped at Jarvie’s store for some whiskey. While Jarvie was in the basement procuring the liquid refreshment, Nicholls decided to help himself to a cigar from a box in the store. Opening the box he was surprised to find it, not full of cigars, but full of gold coins. Whether his story is factual or not, Nicholls believed it, and in later years he came to the Jarvie place with a metal detector searching for the buried treasure. [177]

Saturday, July 3, 1909: William King, a sheepman, met Hood and his partner, who has been identified as Bill McKinley, Hood’s brother-in-law, [178] in Rock Springs. They told King that they were heading into Brown’s Park to look for a job herding sheep. [179]

Sunday, July 4, 1909: Hood and McKinley left Rock Springs on foot for Brown’s Park. Enroute they met cowboy Charlie Teeters on his way to Rock Springs by wagon. He recalled that they were evasive about their future plans and that they were both “dressed in shoes, and gray pants and shirts.” [180]

Tuesday, July 6, 1909: The pair reached the Jarvie ranch. John Jarvie was alone, his sons having all left home to work on other ranches in the vicinity. It was dinner time and Jarvie, displaying his usual hospitality, set out two extra plates for his guests. The dinner was never eaten. The visitors took Jarvie into the store and forced him to open the small safe. [181] The safe was nearly empty because Jarvie had recently been to Rock Springs to pay up his annual accounts there. It contained only a one hundred dollar bill and a pearl handled revolver. [182]

A brief struggle ensued and the old man pulled free of his captors and fled the store. He made it as far as the small bridge which crossed his irrigation ditch where his life was ended by two bullets from behind. [183] One bullet entered his back between the shoulder blades, another entered his brain. [184] The killers grabbed their victim by the heels and dragged his body from the bridge, around the stone house, and down to the river bank where a boat was tied, leaving behind a trail of blood and patches of his long white hair which snagged on obstacles along the path. [185] They tied the body into the boat with a length of clothesline which they had gotten from the store and then pushed the boat into the river with one of the teepee poles Jarvie had kept on hand. [186] Their obvious hope was that the boat would be destroyed in the rapids downstream as it passed through the Gates of Lodore and wipe out all evidence of their crime.

| Photo 30. The Jarvie safe which yielded only a one-hundred dollar bill. (Photo Credit: Glade Ross Collection). |

The killers then turned their attentions to the store. They ransacked it and carried out as much as two men could manage. Their loot included “flour, canned goods, coffee, rope, hopples [hobbles], shoes, underwear, shirts, [and] gloves” [187] which they loaded onto Jarvie’s horse along with Jarvie’s saddle and a saddle belonging to Speck Williams. [188] As they were packing up a new pair of hobbles, they noticed that the death boat had drifted into an eddy a short distance from the store. They laid the hobbles down on a log, forgetting them, and shoved the boat back into the current and it started its voyage a second time.

The two men, on foot, and the heavily burdened horse left the Jarvie ranch and followed the river about one mile southeast to the nearest ranch, the Kings’. They had hoped to steal additional horses there but found none. They then cut the ropes binding the pack onto the horse, both mounted it, and left behind their pile of plunder.

During their evening’s work, the killers’ clothing had become soaked with blood. They removed them, hid them in some bushes as they headed up Jesse Ewing Canyon, and donned new clothing taken from the store. [189]

They passed a ranch about twelve miles out and “the man there said that about daylight his dogs barked and upon looking out he saw two men on one horse at the lower end of his field, and as soon as he went out of the house, they went on around the fence and headed north.” [190]

The stolen horse had been so heavily loaded and ridden so hard that it finally either died or collapsed from exhaustion and the killers continued their getaway on foot. [191]

Wednesday, July 7, 1909: Charlie Teeters, now on his way back to Brown’s Park from Rock Springs, again met the two men on the trail. He later recalled that “They had on new boots, new shirts, and pants” and they said “they were going to Rock Springs for work.” [192] Teeters, of course, was not aware of the murder at that time.

About sixteen miles from Rock Springs, the pair met William King and “in a short conversation with them, they said they had been out to the first ranches, but took a notion to go back to the railroad and get work. It was not until the next day, Thursday, that he arrived at home and learned of the murder.” [193] Thus, ironically, the killers has passed two Brown’s Parkers who could have helped to apprehend them, but neither knew of the murder.

The crime was finally discovered when one of the Jarvie boys, either John Jr. or young Jimmy, or possibly Johnny Law, stopped by the ranch and discovered the store in shambles and the bloody trail leading to the river. [194]

The alarm was quickly spread and the search for the killers was begun. Neighbors immediately took boats and began to patrol the river for signs of the missing skiff and the old man’s body. [195] Ann Bassett was at Mandy Lombard’s place on Willow Creek when a messenger with the grim news dashed through on his way to alert Tom Jarvie who was with a cattle drive on the way to Maybell, Colorado. Ann and Mandy hurried to the Jarvie place where they saw that the chores for the night before had been done and “places for 3 set on the table . . . . Further searching showed where Mr. Jarvie’s body had rested in wet sand along the river bank. Even the depressions from the rivets on his pants showed up” and where the “hole in the back of his head [had] rested.” [196]

The alerted neighbors scoured the area and soon found the new pair of hobbles which the killers had placed on the log next to the eddy when they pushed the boat into the river the second time. In the afternoon, one of the Jarvie sons hurriedly left to notify the officials in Rock Springs.

Thursday, July 8, 1909: The murderers reached Rock Springs, tired and dusty, about one o’clock in the morning and checked into a rooming house.

One of them left a call for seven o’clock in the morning; the other was heard to get up about 10 o’clock. The latter had inquired about the first train east and had been told it would pass through about 11 o’clock. John Jarvie, Jr., had reached Rock Springs at about 10 o’clock that morning to give the alarm; but it took an hour or so before he could get hold of the officers and in the meantime, the two fellows had gotten away. [197]

Shortly thereafter, one of the murderers asked storekeeper George Lohman in Point of Rocks, east of Rock Springs, to change a hundred dollar bill. [198]

Minnie Crouse, who was homesteading at Minnie’s Gap, had not heard about the murder. She rode into Brown’s Park to return a book that John Jarvie had loaned her. She found the Jarvie place quiet and deserted when she arrived but saw that “something had gone wrong . . . . I saw where they had had the row on the little bridge . . . his long white hair was caught on many things and I walked around the rock house to the boat . . . . They must have had him by the heels, just dragged him that way . . . you could see plainly where they dragged [him].” [199]

News of the deed reached Vernal on this day via a telegram sent from Rock Springs which had to be wired from Rock Springs to Ogden to Salt Lake City to Mack, Colorado, and finally to Vernal. It simply read “John Jarvie murdered at Bridgeport. Body adrift in boat. Two young men suspected. Heading this way, sheriff here notified.” [200] Sheriff Richard Pope of Uintah County left immediately in the night on horseback for the scene of the crime.

Once in Brown’s Park, he thoroughly investigated the area. He and Josie Bassett and one other found the tracks of the killers and trailed them to the spot where they had abandoned their plunder near the King ranch. From a distance Josie thought the piles of goods resembled two men sitting down and leaning over. [201] They continued to follow the tracks up Jesse Ewing Canyon where they discovered the bloody clothes abandoned in the bushes. Pope did not, however, continue on to Rock Springs, assuming the officials there were, by now, doing all they could to apprehend the killers. Before leaving Brown’s Park he was informed that Jarvie’s horse had been found where the killers had left it and he had the following notice printed and distributed:

WANTED — Two young men for the murder of John Jarvie, at Bridgeport, Utah, on July 6th, 1909. George Hood, height about 5 ft. 6 or 7 in., weight 150 or 160 lbs. sallow complexion, heavy eyebrow, brownish hair, has blue gray eyes that look peculiar, high and wide cheek bones and face tapers to point of chin, upper lip thin and lower lip and chin protrudes, has tatoo on back of hand and runs up the arm, age about 27. His partner 5 ft. 7 in. light complected, thin weight 140 lbs. light clothes, pants are corduroy or Kakie, 6 or 6-1/2 shoe. Both were smooth shaved and wore curved pointed shoes. [202]

A young man named Joe Nelson was walking from Lander, Wyoming to Utah and was arrested and imprisoned in Rock Springs because he fit the description of one of the killers. George Lohman, of Point of Rocks, visited the prison and he immediately declared that Nelson was not the man who had asked to change the one hundred dollar bill and Nelson was released. [203]

Friday, July 9, 1909: Two more men were arrested in Rawlins, Wyoming, but they were not the wanted men either. [204]

Thursday, July 14, 1909: John Jarvie’s body was finally found by his son, Archie. [205] The boat in which it was tied had become caught in some willows about twenty-five miles from where it had been sent down the river not far from the entrance to the Gates of Lodore. One account says the boat was found upside down with the body still tied into it [206] while another says the body had fallen from the overturned boat and the clothing had caught in the brush as it drifted toward shore. [207] Crawford MacKnight was among the crowd of fifteen to twenty people who had gathered on the shore to witness the recovery of the body. [208] The corpse was badly disfigured. “The body was so swollen they couldn’t get it into the box they had made for him.” [209] Herb Bassett had them wrap it in a tarp and a big box was constructed at the nearby Bassett ranch. [210] He was buried in the Lodore Cemetary not far from where the body was discovered.

By August 11, the posse that had been pursuing the murderers had given up the search [211] and although a $1,000 reward was offered ($500 from Governor Cutler of Utah and $500 from the people of Rock Springs [212]) the killers had escaped.

Young Jimmy Jarvie kept up the search and relentlessly stuck to the killers’ trail. He sent at least one dispatch enroute from Kemmerer, Wyoming, having traced the murderers to that point. [213] He eventually arrived in an Idaho town (either Montpelier [214] or Pocatello [215]) to which he had tracked them. He retired to a room in a hotel there. Anxious to rid themselves of this tireless pursuer, his father’s murderers stole into his room and shoved him from the second floor window. He landed on his head and was killed instantly. [216]

A postscript to the story comes from George Stephens, who had been Under Sheriff of Daggett County for many years. In 1935 while riding on a train from Denver to Green River, he sat next to an Italian man and they began to discuss the history of the area. The Italian informed Stephens that he worked for the Southern Pacific Railroad in Sparks, Nevada, where a co-worker had boasted for years that he had committed a murder and a robbery in Brown’s Park and had never been apprehended.

Stephens began to investigate the story and, working with Nevada officials, came to the conclusion that the boastful railroad worker in Sparks was probably, indeed, one of Jarvie’s killers. Stephens approached Tom Jarvie, the only Jarvie son still living in the area at that time, but Tom was convinced that it would be useless to pursue the matter further and the investigation came to a halt. [217]

A glowing tribute to John Jarvie appeared on the front page of the Vernal Express July 30, 1909, which included the following:

It is hard to imagine John Jarvie dead. Harder still to think of him murdered. He was the sage of the Uintahs, the genius of Brown’s Park. He could almost be called the wizzard of the hills and river. He was not only a man among men but he was a friend among men . . . .

He kept a ferry; but he was more than a ferryman; he kept a store, but he was not circumscribed by the small scope of a storekeeper.

He was as broad and generous as far reaching in his good deeds as the stream which he knew and loved as a brother and over whose turbulent waters he had helped so many travelers and upon whose unwilling bosom he was set adrift to seek an unknown grave . . . .

The tribute draws upon Jarvie’s own words for a conclusion; words from the tribute that Jarvie had made to his long time friend, Mrs. Mary Crouse, when she died in 1904:

Here in this world where life and death are equal kings, all should be brave enough to meet what all have met—from the wondrous tree of life the buds and blossoms fall with ripened fruit and in the common bed of earth patriarchs and babes sleep side by side.

It may be that death gives all there is of worth to life. If those who press and strain against our hearts could never die perhaps that love would wither from the earth. Maybe a common faith treads from out the paths between our hearts the weeds of selfishness and I should rather live and love where death is king than have eternal life where love is not. Another life is naught unless we know and love again the ones who love us here.

The largest and nobler faith in all that is and is to be, tells us that death even at its worst is only perfect rest—we have no fear; we all are children of the same mother and the same fate awaits us all. We, too, have our religion and it is this: ‘Help for the living, Hope for the dead’.

“Those words spoken by Mr. Jarvie not only give an idea of his own nature but they are especially appropriate in his own sad ending. May his body rest in place near the Green River and in the pleasant vale between the hills, where history will be incomplete without the last thirty years of the life story of John Jarvie.”

Contact Us

If you have questions or would like to check availability, call 970.926.0216 or complete the contact form.